The United States went through a period of substantial political change during the American Civil War, which took place from 1861 to 1865. It ultimately led to the end of slavery and the maintenance of the Union as a political entity.

In addition, the war had a significant effect not only on the rights and status of African Americans, but also on the formation of the federal government of the United States and its relationship with the states.

In addition, more than 620,000 people, both military personnel and civilians, lost their lives during the American Civil War, making it one of the bloodiest wars in the history of the United States.

There were quite a few veterans who would become presidents with many of them serving as officers during the war.

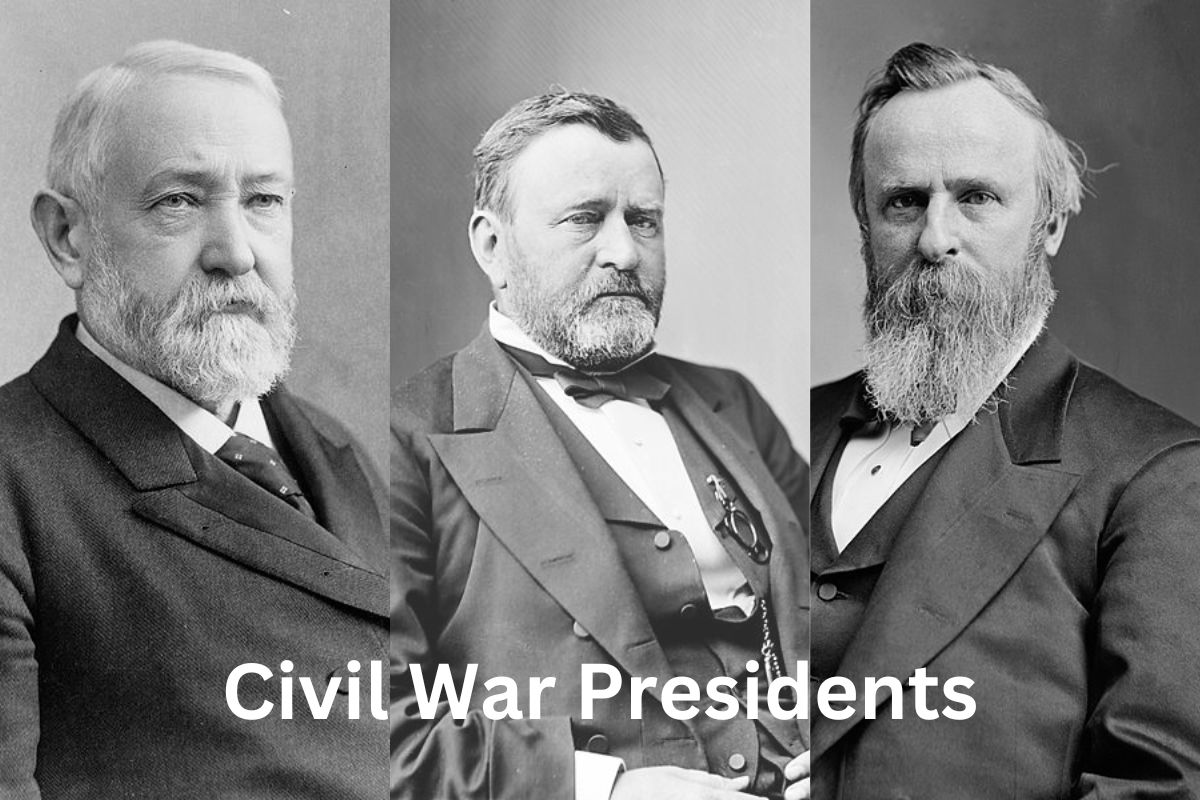

Civil War Presidents

1. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses Sidney Grant was an American military commander and politician who served as the country’s 18th president from 1869 through 1877. Grant was born on April 27, 1822, and passed away on July 23, 1885.

After achieving victory as Commanding General of the Union Army in the American Civil War in 1865, he went on to serve as the Secretary of War for a short period of time.

Later, when he was president, Grant was a successful civil rights executive. He signed the act that founded the Justice Department and worked with Radical Republicans to defend African Americans during Reconstruction. Both of these accomplishments occurred during his tenure.

Grant, who was born and raised in Ohio, possessed a remarkable skill when it came to horses. After being accepted to West Point, Grant graduated in 1843 ranked 21st in his class and went on to serve with distinction in the Mexican-American War.

In 1848, he wed Julia Dent, and the pair went on to have four children together. In 1854, Grant handed in his resignation from the army and went back to live with his family, despite the fact that they were poor.

Soon after the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, he enlisted in the Union Army and quickly rose to prominence by achieving a string of early successes for the Union in the Western Theater.

Also Read: Interesting Presidents Day Facts

The Vicksburg campaign that he led in 1863 was successful in seizing control of the Mississippi River, which dealt a huge strategic blow to the Confederacy and effectively split it in two. After the victorious conclusion of the Battle of Chattanooga, President Abraham Lincoln promoted him to the rank of lieutenant general.

Grant was engaged in combat with Robert E. Lee for a total of thirteen months, including the bloody Overland Campaign and the siege of Petersburg. After Lee had fled Petersburg, Grant defeated him at the Battle of Appomattox. On April 9, 1865, General Grant accepted General Lee’s formal surrender.

A week later, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, and his successor, President Andrew Johnson, promoted Ulysses S. Grant to the rank of general in the army in 1866. Later on, Grant publicly disagreed with Johnson’s position regarding Reconstruction.

Grant used the Reconstruction Acts, which were passed despite Johnson’s veto, to enforce civil rights for newly freed African Americans. Johnson was unable to override Grant’s use of the Reconstruction Acts.

Also Read: Reconstruction Era Facts

Grant, a war hero who was drawn into the conflict by his sense of duty, was nominated for president of the United States by the Republican Party and went on to win the election in 1868.

As president, Grant was instrumental in the postwar economic recovery of the nation, the passage of the 15th Amendment, and the eradication of the Ku Klux Klan. He also fought for the reconstruction of Congress.

Under Grant’s leadership, the Union was completely reconstructed. He promoted African Americans and Jewish people to influential posts in the government.

2. Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th President of the United States from 1877 to 1881, following terms in the United States House of Representatives and as Governor of Ohio.

Prior to the American Civil War, Hayes was a lawyer and ardent abolitionist who represented fugitive slaves in court. Before taking office, he served in the Union Army and the House of Representatives.

His administration marks a watershed moment in American history, as historians believe it to be the formal conclusion of Reconstruction. Hayes, a major member of the Republican “Half-Breed” party, appeased both Southern Democrats and Whiggish Republican merchants by stopping the federal government’s engagement in the South’s efforts to achieve racial equality.

As an attorney in Ohio, Hayes served as the city solicitor of Cincinnati from 1858 until 1861. He quit a promising political career to join the Union Army as an officer at the commencement of the American Civil War.

Hayes was wounded five times, the most badly in 1862 during the Battle of South Mountain. He rose through the ranks due to his fighting gallantry and was elevated to brevet major general. Following the war, he was a Republican in Congress from 1865 to 1867.

Hayes left Congress to run for governor of Ohio, where he served two terms in a row from 1868 until 1872. Before being sworn in as president, he served part of a third two-year term from 1876 to 1877.

Following the 1876 United States presidential election, one of the most controversial in U.S. history, Hayes ascended the presidency in 1877. Hayes was defeated in the popular vote by Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, and neither candidate received enough electoral votes to win the election.

If no candidate wins the Electoral College, the House of Representatives is responsible with picking the next president, according to the United States Constitution. In the Compromise of 1877, a Congressional Commission granted Hayes 20 contested electoral votes, ensuring his victory.

The electoral squabble was settled in a backroom arrangement in which the southern Democrats agreed to Hayes’ election on the condition that he stop government backing for Reconstruction as well as military presence in the former Confederate States.

Hayes’ administration was influenced by his belief in meritocracy and equitable treatment regardless of money, social rank, or color.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was one of his presidency’s defining events, which he concluded by mobilizing the US Army against the railroad workers. It is still the worst confrontation in American history between workers and strikebreakers.

Hayes initiated modest civil-service reforms while president, laying the framework for additional reform in the 1880s and 1890s.

3. James Garfield

James A. Garfield was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months later on September 19, 1881 (two months after being shot by an assassin). He was born on November 19, 1831.

He was the only sitting member of the House of Representatives to be elected president, and he was a lawyer and Civil War officer. He was a congressman for nine years.

He first gained political success by being elected to the U.S. Congress before making a run for the presidency. Having become president-elect, he turned down Ohio’s nomination for a Senate seat.

Garfield believed that the rebel leaders had lost their constitutional rights and that elimination of slavery should be the priority. He advocated for the confiscation of Southern plantations and the expulsion or execution of rebel leaders as means to ensure the permanent eradication of slavery.

The burden for “establishing what laws is necessary to provide equal justice for all loyal individuals, whatever of color,” as Garfield put it, lay squarely at the feet of Congress. He backed Lincoln more strongly when the president took decisive measures to end slavery.

4. Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison, born on August 20, 1833, and passing away on March 13, 1901, was the 23rd president of the United States, holding office from 1889 to 1893.

He was a descendant of two American presidents’ families, being the grandson of William Henry Harrison (the ninth) and the great-grandson of Benjamin Harrison V (the fifth).

Harrison attended Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, after being born on a farm near the Ohio River. After relocating to Indianapolis, he became well-known in the community and went on to achieve success in the fields of law, church leadership, and politics.

Following his service as a colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War, he was promoted to the rank of brevet brigadier general of volunteers by the U.S. Senate. In 1876, Harrison made an unsuccessful bid for governor of Indiana. From 1881 to 1887, Harrison served in the Senate after being elected to a six-year term by the Indiana General Assembly.

Although he lost the popular vote to Grover Cleveland, Republican candidate William Henry Harrison was elected president in 1888.

The McKinley Tariff, which set new standards for protective trade rates, and the Sherman Antitrust Act were both landmark pieces of legislation passed during Harrison’s presidency. By modifying the Land Revision Act of 1891, Harrison helped bring about the establishment of the nation’s forest reserves.

Six western states were admitted to the Union during his presidency. Even though Harrison greatly improved the U.S. Navy and pursued an aggressive foreign policy, he was unable to get federal funds for education or enforce voting rights for African Americans despite proposing both.

5. William McKinley

William McKinley served as the 25th President of the United States from 1897 until his assassination in 1901 (born January 29, 1843; died September 14, 1901).

He orchestrated a political realignment that made the Republican Party the dominant one in the industrial states and the country as a whole until the 1930s.

He oversaw the U.S. victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898, which gave the United States control of Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Cuba, lifted the economy out of a deep depression, kept the country on the gold standard despite widespread support for free silver, and boosted industry and wages through protective tariffs.

Also Read: Spanish American War Facts

McKinley, a Republican, served in the Union Army during the American Civil War and was the last president to have done so. He was also the only president to have served in the military from the rank of private to that of brevet major.

He eventually married Ida Saxton and opened a law practice in Canton, Ohio after the war. McKinley ran for Congress and won in 1876, promising to deliver prosperity through a protective tariff he helped create as the party’s leading expert.

His infamous 1890 McKinley Tariff, along with gerrymandered congressional districts drawn by Democrats to ensure his defeat, led to the Democratic Party’s landslide victory that year. He served as governor of Ohio twice (1891 and 1893), both times striking a balance between business and labor.

Also Read: Accomplishments of William McKinley

While the country was in the midst of a severe economic downturn in 1896, he was able to gain the Republican nomination for president with the help of his trusted advisor, Mark Hanna.

In a front porch campaign where he championed “sound money” (the gold standard unless changed by international agreement) and promised that high tariffs would restore prosperity, he defeated his Democratic opponent William Jennings Bryan.

The economy expanded rapidly under McKinley’s administration. To shield domestic manufacturers and manufacturing workers from cheap imports, he advocated for and helped establish the 1897 Dingley Tariff and the 1900 Gold Standard Act.

6. Chester A. Arthur

American lawyer and politician Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was the 21st president of the United States, in office from 1881 to 1885.

Previously, he was Vice President under President James A. Garfield, making him the 20th VP in American history. Arthur ascended the President upon Garfield’s death in September 1881—two months after being shot by an assassin.

Although Arthur’s family eventually settled in New York City, he was born in Fairfield, Vermont. During the American Civil War, he led the New York Militia’s supply corps as its quartermaster general.

Following the war, he devoted more effort to New York Republican politics and quickly advanced in Senator Roscoe Conkling’s political organization. He was a major backer of Conkling and the Stalwart wing of the Republican Party, and President Ulysses S. Grant named him Collector of the Port of New York in 1871.

As part of an effort to reform the federal patronage system in New York, President Rutherford B. Hayes sacked Arthur in 1878. In 1880, the Republicans nominated Garfield for president, and Arthur, an Eastern Stalwart, was chosen to serve as his running mate. A little over four months into his presidency, Garfield was shot and killed by an assassin; 11 weeks after his death, Arthur took office.

Arthur had a tough time at first due to his association with the notorious Conkling and the Stalwarts. Reformers were taken aback by his support for and implementation of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act.

Although he oversaw the revitalization of the United States Navy, he was panned for doing nothing to reduce the government budget surplus that had been building up since the end of the Civil War.

A twenty-year prohibition on Chinese immigration to the United States was included in the original version of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which Arthur vetoed on the grounds that it was in violation of the Burlingame Treaty, but he approved the second version, which had a ten-year limit.

Arthur, who was in terrible health, barely campaigned for the Republican candidacy in 1884 and then retired at the end of his tenure. Arthur’s government was less active than a modern presidency due to his declining health and political temperament, yet he nevertheless received high marks from his contemporaries.

Despite this, most contemporary historians view Arthur’s presidency as below par, and Arthur himself as one of the least remarkable heads of state.